Overview of Renaissance Periods

APPROACHING PERIODS AND STYLES

Problems with Defining Stylistic Periods

Most of the stylistic labels applied to architecture are broadly based and also apply to other cultural forms like literature and music. Because bursts of creativity occur in the various arts at different times, the dates assigned to stylistic periods cannot be regarded as corresponding exactly to any single discipline. The problem is further complicated by the fact that different regions or cities developed at different paces.

Labels

The Italian Renaissance is generally subdivided into periods that are commonly referred to both by century and by more descriptive names like "High Renaissance." The Italian terms for the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries, Trecento (1300s), Quattrocento (1400s), and Cinquecento (1500s), are also used as period labels.

Renaissance specialists differ in their designation of labels and dates, and the choice may vary according to the discipline under consideration.

The Trecento (14th century)

The Trecento was a period of stylistic transition.

Manifestations of what would become termed the Renaissance were present in the work of painters like Giotto and writers like Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. However, in the same years artists such as Simone Martini worked within a style that is generally termed "International Gothic." Thus the period has come to be called both "Early Renaissance" and "Late Gothic" depending on the characteristics that dominate, and on the historical views of the writer. For instance, the use of "Late Gothic" tends to emphasize the continuity of art from this period with that of the preceding period of "High Gothic" whereas the use of "Early Renaissance" suggests a break with the preceding century.

Although the presence of Renaissance traits in the work of certain 14th-century painters may justify the Early Renaissance label for that field, the same cannot be said for the architecture of that century, when little besides a greater interest in exterior symmetry anticipated the Renaissance style.

The Quattrocento (15th century)

The fifteenth century saw the full flowering of what has come to be called the "Early Renaissance."

The two terms, "fifteenth century" and "Early Renaissance," are often used interchangeably, although it is important to note that temporal and stylistic labels never fit together seamlessly. Leonardo da Vinci, the first "High Renaissance" artist, began most of his major works in the last two decades of the fifteenth century.

The Cinquecento (16th century)

There were two main co-existing tendencies in 16th-century architecture.

The first of the two tendencies was oriented toward classicism and was approached by studying ancient models and writings on architecture, which included, above all, Vitruvius' De architectura. Ultimately this approach led to bodies of rules such as Vignola's Regola (Rules of the Five Orders of Architecture).

The second of the two 16th-century tendencies was oriented toward fantasy and the imagination, which was allowed free expression in modifying traditional forms and inventing new ones. This style also relied on a defined body of rules that once accepted, could be subverted. Novelty was considered to be a virtue.

The two main stylistic categories of the first half of the sixteenth century are "High Renaissance" and "Mannerism." Although the classically oriented tendency dominated in High Renaissance architecture and the imaginatively oriented tendency realized its fullest expression in Mannerist architecture, both tendencies were present during both stylistic periods.

Mannerism continued to be a force in the second half of the century. The term "Late Renaissance" refers to works of this period that are not Mannerist. Many Late Renaissance works have characteristics that anticipate the coming Baroque style.

THE EARLY RENAISSANCE, 1420-1495

Architectural Pioneers

Early Renaissance architecture was conceived in terms of planes and modules using a vocabulary based on the orders of ancient Roman architecture. The most influential architects of this period were Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti.

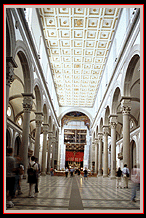

Brunelleschi used modules and proportions based on simple ratios to determine dimensions. The contrast between the white plaster walls and dark gray stone used for the columns and trim in many of his structures enhanced the clarity of his designs. Although Brunelleschi sought to emulate ancient architecture, his work also shows the influence of the Tuscan-Romanesque style. (In Brunelleschi's day, there was a great deal of confusion about past architectural styles and their dates, and the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral was thought be Roman.)

Alberti, who was not trained professionally as an architect, brought an archaeologically oriented perspective to his examination of Roman ruins. His scholarship in Classical studies enabled him to read Latin works by Vitruvius and other Roman authors who wrote about architecture. In addition to utilizing a vocabulary based on the orders, Alberti's work incorporates Roman building types like the triumphal arch and the temple front. His treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria, was written in the 1450s and known by many of his circle from hand-written copies. Its publication in 1485 led to widespread influence.

Important Sites

Some elements of Brunelleschi's style were spread to other parts of Italy by his followers.

Because his work as a papal secretary involved his traveling and living in different parts of Italy, Alberti had opportunities to design buildings in several parts of Italy.

●Florence. The first flowering of Early-Renaissance architecture occurred in Florence in the work of Brunelleschi, which includes important churches and chapels. Alberti built two important façades in Florence for the powerful Rucellai family: the Palazzo Rucellai, which demonstrated the influence of ancient Roman architecture and was itself highly influential, and Santa Maria Novella, which consists of a classical framework overlaid on a pre-existing structure. The architect Michelozzo is important as the architect of the Palazzo Medici, which influenced the design of local palaces, and the library at the Monastery of San Marco, which influenced the plans of later Renaissance libraries. At the end of the century, Giuliano da Sangallo designed two trend-setting buildings near Florence: the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano, which was the first villa to include a pediment in its façade, and Santa Maria delle Carceri at Prato, a centralized church that incorporated many of Alberti's recommendations.

●Mantua. Mantua was an important architectural site in the fifteenth century because of the work of Alberti. At the church of Sant' Andrea, which was patterned after the Basilica of Constantine, Alberti followed Roman precedent in using a vaulted ceiling and piers to carry the nave arcades instead of a flat ceiling and columns. At San Sebastiano, Alberti's only centralized church, he used a Greek-cross plan and based the building's proportions on simple ratios.

●Milan. Brunelleschi's influence was visible in Milan in the work of Filarete, who worked for the Sforza family and designed the Ospedale Maggiore. Later in the century, Ludovico Sforza commissioned Bramante's earliest architectural work, the remodeling of Santa Maria presso San Satiro. At Santa Maria delle Grazie, another of Ludovico's commissions, Bramante added a chancel that was conceived in volumes rather than planes and whose parts flowed together in an organic manner. In Milan Bramante would have known Leonardo da Vinci, who explored this volumetric quality in both sketches of buildings and studies of figures. Their work contributed to the formation of the style known as the High Renaissance.

●Pienza. Pope Pius II, who was born in Corsignano, rebuilt the town as Pienza. He engaged Bernardo Rossellino to design new buildings and a new civic piazza that was trapezoidal in shape. Building a piazza and most of its buildings in a single building program was a milestone in urban planning.

●Rome. Much of Rome's architectural development in the fifteenth century was initiated by popes and cardinals. Alberti's influence is evident in many ecclesiastic commissions such as the building or remodeling of palaces and churches. He is also credited with inspiring the revival of the ancient Roman practice of using the orders to decorate piers, which made its first appearances at the Benediction Loggia and the Palazzo Venezia.

●Urbino. Urbino's Palazzo Ducale was a large project that involved several architects over a long period. The most important architects to work on the site were Luciano Laurana and Francesco di Giorgio, who both worked in several parts of Italy.

●Venice. In Venice, the influence of Alberti's façade designs for the Malatesta Temple and the Palazzo Rucellai can be seen on Mauro Codussi's façades for San Zaccaria and the Palazzo Vendramin-Calergi.

●Vigevano. Vigevano, a town southwest of Milan, is significant as the site of the first loggia-surrounded piazza built since ancient times. Although there is no documentary evidence, it is widely assumed that the architect of the Piazza Ducale was Bramante, who worked for its patron, Ludovico Sforza, and was in Vigevano at the time it was built.

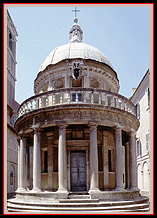

Leadership during the High Renaissance

High-Renaissance architecture embodied harmony and balance on a monumental scale. Bramante led the way using a new dynamic approach to design in which parts flowed together organically and the architecture overall was more sculptural. His use of the orders followed Vitruvius' treatise more closely than that of anyone before him. Bramante's mature work epitomized the Classical impulse in its purist form, stripped of ornamentation except that of the orders. Especially influential was his design for the crossing piers of St. Peter's, whose inner faces are perpendicular to the dome's radii, thus allowing the dome to be larger than it could be using square piers.

Bramante's protégé Raphael showed the influence of his teacher in his early work.

Important Sites

●Rome. Rome became the art center of Italy in the early sixteenth century because Pope Julius II, who envisioned re-creating the splendor of ancient Rome, employed the most talented artists of central Italy. Bramante, who had already come to Rome following the French conquest of Milan in 1499, first designed the cloister of the Monastery of Santa Maria della Pace and the Tempietto at the Monastery of San Pietro in Montorio. Beginning in 1505, Pope Julius commissioned Bramante to make several major additions at the Vatican including a new St. Peter's, a facade for the Vatican Palace, and a 1000-foot long court. Bramante also designed a highly influential domestic palace, the Palazzo Caprini. Raphael's architectural works in Rome included the Chigi Chapel and the Villa Madama. Because he took models from the most splendid period of Roman history, that of the Empire (established in 27 BC), Raphael's work is more ornamental than Bramante's.

●Todi. The rigorously centralized design of Cola da Caprarola's Santa Maria della Consolazione at Todi is thought to have originated in Bramante's circle because of its general simplicity and use of a cubical core like the one Bramante designed for Santa Maria delle Grazie.

Invention

Because Bramante's work followed a closed system of guidelines, further development along the lines he established would have been formulaic and redundant, which made variation from Classical models inevitable. Experimentation is first seen in the works of Bramante's followers: Raphael and his assistant Giulio Romano.

Mannerist architects reached beyond the boundaries of Classical architecture in inventing new forms and breaking the rules governing the orders and their proportions. A knowledge of the norms or rules underlying Classical architecture was required for the viewer to appreciate the ingenuity of the deviations, which ranged from the creative or novel to the prankish or perverse.

Early Mannerists

Mannerism had roots in the Roman work of Raphael and Giulio Romano and in the Florentine work of Michelangelo. Many of the most important Mannerist architects of the first half of the sixteenth century had originally been Bramante's followers. In the 1520s they dispersed to other parts of Italy and went on to develop their own individual styles, which varied considerably but included elements of Mannerism.

Degrees of Mannerism

Not all architects who produced Mannerist works were committed to this style exclusively. Although Mannerist elements can be found during the second half of the sixteenth century in works by Michelangelo and Giacomo Vignola, both also designed buildings without conspicuously Mannerist features during this period as demonstrated by the Palazzo della Conservatori and the Villa Farnese.

Much of the same can be said of the architecture of Andrea Palladio, whose buildings ranged from Classically based to overtly Mannerist.

Important Sites

●Rome. Early Mannerist works in Rome include Raphael's Palazzo Branconio dell' Aquila, which has been destroyed, and Giulio Romano's Palazzo Maccarani.

●Florence. In Florence, Michelangelo's Mannerism is evident in the many unusual forms in the Medici Chapel and the novel arrangement of features in the Laurentian Library. Mannerism was later embodied by Ammanati's courtyard of the Palazzo Pitti, as well as Vasari's Uffizi Palace, and Buontalenti's Porta della Suppliche at the Uffizi.

●Mantua. In Mantua, Giulio Romano's Mannerism is readily seen at the Palazzo del Tè and his own house.

●Venice. In Venice, Mannerism was introduced in the work of Jacopo Sansovino, who was the city's chief architect for most of his 43-year long career there.

●Verona. In Verona, Sanmicheli's Palazzo Bevilacqua incorporated many Mannerist features.

●Vicenza. In Vicenza, Mannerist features can be seen on Palladio's Palazzo Valmarana and Loggia del Capitaniato.

LATE RENAISSANCE, 2nd half 16thc.

Labels

The label "Late Renaissance" is often used in connection with works from the second half of the sixteenth century. Works of this period are distinguished from those of the High Renaissance through their use of forms that would become typical of the later Baroque era such as oval ground plans.

Treatment of Bays

One feature marking the change in style is the treatment of individual bays. In the fifteenth century, the bays of a building were generally similar to each other in design without regard to whether they contained windows or doors, but in the sixteenth century, door-filled central bays, and often, outer bays as well, were different from the others.

Bays were accentuated by increases in their width or ornamentation.

Outward projection from the wall plane was used to accentuate bays on the corners or in the center.

Quoins were a common form of accentuating central bays and corners.

Influence of the Counter Reformation

The Counter Reformation affected architecture and its decoration in several ways.

●Building and remodeling churches. Under the influence of recommendations made after the Council of Trent, church design underwent many changes in the second half of the sixteenth century. Church interiors were designed to improve the worshipper’s ability to see and hear the services. Plain whitewashed walls were often adopted because they were less distracting than elaborate fresco decoration, and some religious images were considered inappropriate and unnecessary. Many churches were remodeled to meet these new guidelines. Notable among new churches is the Jesuit home church, Il Gesù, which became a trend-setting model for churches in Italy and around the world. Its influence was fostered through the generous funding of the Jesuit Order by several of the reformer popes. Gregory XIII funded the Order to carry out his program of establishing colleges for training the clergy and building missionary posts in the Americas and the East.

●Rejecting pagan models. Architectural reference to the Classical past declined as reformer popes like Paul IV and Pius V rejected Classical art as pagan. They gave away many ancient statues of nude figures, and Sixtus V closed the sculpture court to visitors because it contained nude statues like the Apollo Belvedere and the Laocoön.

●Promoting pilgrimage sites. To stimulate the faithful to make pilgrimages to Rome's titular churches, many were rebuilt and made more accessible by enlarging their piazzas and building wide streets to connect them.

●Modifying domestic patronage of church officials. Reforming the Church involved changing the lifestyles of the clergy because many church officials were known for their lavish lifestyles and splendid palaces. The two most magnificent gardens of the Italian Renaissance, the Villa d'Este and the Villa Lante, were built by Cardinal Este and Cardinal Gambara. Pope Gregory XIII criticized the latter's lavish spending on the villa by saying that the money would have been better spent on charitable causes. Cardinal Gambara left it unfinished and later contributed to the rebuilding of the local hospital and church. At the end of the century, the popes themselves made changes at the Vatican's Belvedere Court because it resembled a villa in having a terraced garden and an open-air theater. Pius V removed the theater seating, and Sixtus V interrupted the courtyard’s thousand-foot expanse with a new wing housing a library.

Important Sites

●Rome. Michelangelo, who was the leading architect in Rome until his death in 1564, worked on St. Peter's, the Piazza del Campidoglio, the Palazzo Farnese, and Santa Maria degli Angeli. He was succeeded at St. Peter's by Vignola, whose other works in Rome include part of the Villa Giulia and the body of Il Gesu, which is significant for having chapels instead of side aisles. Giacomo della Porta completed the dome of St. Peter's and designed the facade of Il Gesu. Late in the century, Domenico Fontana built papal palaces and carried out many piazzas and fountain projects for Sixtus V that changed the public face of Rome.

●Florence. In the second half of the century, the leading architects of Florence all worked for Grand Duke Cosimo I de' Medici. Bartolommeo Ammannati enlarged the Pitti Palace with a courtyard and other rooms. Giorgio Vasari built the Uffizi Palace and began the Great Grotto, which Bernardo Buontalenti completed.

●Vicenza. Vicenza is an important center of architecture because of the work of Andrea Palladio, who built civic palaces, private palaces, and villas there.

●Venice. After Sansovino's death in 1570, Palladio became Venice's unofficial municipal architect. His churches San Giorgio Maggiore and Il Redentore both conform to the Trent guidelines. Additionally, the use of interlaced temple fronts on their façades offers a harmonious solution to the problem of applying Classical design to the façade of a basilica, whose two levels of roofs make its shape irregular.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back