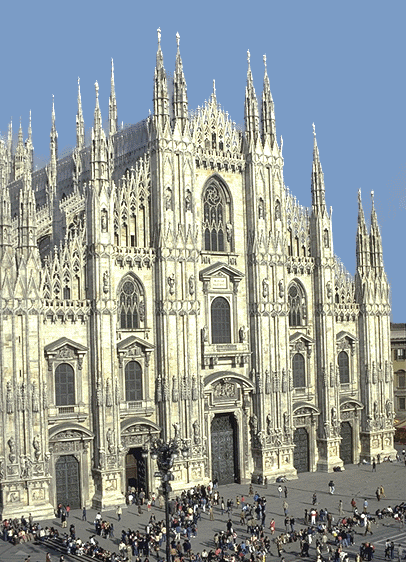

Milan Cathedral

Begun 1385

BACKGROUND

Commission

In 1385, Giangaleazzo Visconti, who had just come to power as the ruler of Milan, decided to replace the old cathedral of Milan with a new one. To fund its construction, he and his cousin, the Archbishop of Milan, appealed to the public for donations. Building a new cathedral was a very popular cause, and much money was raised.

Selection of the Gothic Style

Milan Cathedral's Gothic styling reflects Giangaleazzo's admiration of the upward-pointing cathedrals of Europe and his desire for Milan to have a similarly impressive cathedral on its skyline.

Foreign Consultants

Because local builders were unfamiliar with Gothic construction, architects who had worked on northern Gothic churches were brought to Milan to work with them. Many conflicts between foreign and Italian architects arose over the years.

Switch from Brick to Marble

Examination of an early section of the foundation reveals that the construction of Milan Cathedral was originally begun in brick and then changed to marble. In 1387, Giangaleazzo ordered the change and signed a contract with a quarry in Candoglia, which was west of Milan in the Piedmont.

At that time, brick was the traditional building material in the Lombard region and stone was primarily used for accentuated supportive members.

SITE

Replacement of Earlier Cathedral

The site was occupied by the old cathedral of Santa Maria Maggiore, a basilica in form. The decision to build a new cathedral followed the failure of recent attempts to repair the aging structure.

As was often the case when a basilica is replaced, much of the older building was left in place for continuing use and torn down in stages as its stone and the land under it were needed for the new building. As was typical, construction began at the east end and progressed westward.

Because the new cathedral was to be much larger than the old one, other buildings, such as the baptisteries of two churches, had to be torn down.

Clearing Space Near Cathedral

The piazza in front of the cathedral was begun in the fourteenth century as a marketplace beside the old cathedral. After beginning the new cathedral, Giangaleazzo expanded the open area by removing two ecclesiastic residences.

Enlarging Piazza in 15th Century

In 1458 the piazza was further enlarged by Francesco Sforza, who received permission from Pope Pius II to remove a church from the site. Pope Pius was especially open to the notion of urban planning because he was in the process of creating a new piazza in his hometown of Pienza, where he was also building a Gothic-style cathedral.

Expanding Piazza after 1861 Unification

After the unification of Italy in 1861, the piazza was radically expanded to reach its present size and form.

In the piazza's center is an equestrian monument, the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, Italy's first king after the unification in 1861. Because of his national importance as the first king and as one of the men who helped achieve unification, monuments were erected to him in many Italian cities.

The large arch on the right side of the piazza is an entrance to the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, a shopping arcade designed in 1861. It consists of four barrel-vaulted wings extending outward from a domed center. Its roofs were built using cast iron and glass, a form that had come into its own recently with the development of greenhouses.

CONSTRUCTION HISTORY

1385: Construction begun

Construction was supervised by the Superstantia, which had administered work on the earlier cathedral, Santa Maria Maggiore. Simone da Orsenigo, who is often credited with the cathedral's plan, was appointed chief engineer. Construction began at the north sacristy.

1387: Fabbrica del Opera established

Giangaleazzo Visconti established the Fabbrica del Opera to replace the old Superstantia. He also called for its building material to be changed from brick to marble.

1389: Bonaventure Designed Apse

The French architect Nicolas de Bonaventure, who was appointed to replace Simone da Orsenigo as chief engineer in 1389, designed the apse.

1391-1400: East End Piers Built and Apse Vaults Begun

Giovannino de Grassi, who was appointed chief engineer of the Fabbrica in 1391, designed the piers. By around the beginning of the fifteenth century, the piers of the east end were standing and the apse vaults had been begun.

1400-1447: Apse Vaults, Transept, and Part of Nave Built

The apse vaults, the transept, and part of the nave were built under the direction of Filippino degli Organi in the first half of the fifteenth century. Visconti support ended in 1447 with the death of Filippo Maria Visconti, the last Visconti ruler.

1450-89: Nave Completed and Old Façade Installed

Francesco Sforza came to power in 1450, and he and his sons after him continued to support the cathedral's construction. To cover the entrance facing of the recently completed nave, the façade of the old church of Santa Maria Maggiore was installed in 1489.

1470: Crossing Reinforced

In preparation for the addition of the lantern, Guiniforte Solari strengthened the crossing by adding round arches above the four pointed ones.

1490-1500: Tiburio Constructed

In 1490, Giovanni Giacomo Amadeo and Giovanni Giacomo Dolcebuono received the commission to build the lantern, commonly called the tiburio. They completed it in 1500.

Early 1500s: First Crossing Spire Built

Amadeo built the first of the four spires that rise above the crossing piers.

1535: Transept Façades Designed

Christoforo Lombardo designed the façades of the transept ends.

1565-1631: Classical Design Adopted

Archbishop Carlo Borromeo, who favored adopting a classical scheme of decoration, appointed Pelligrino Tibaldi chief engineer and directed him to produce a new design along classical lines. Construction according to Tibaldi's design continued through the terms of Archbishop Carlo Borromeo and his nephew and successor, Archbishop Federico Borromeo. During this period, the façade was begun and much of the east end was completed, including a tabernacle above the altar, two pulpits attached to crossing piers, and the canons' choir.

Early 1600s: Façade Begun

The façade was begun in the early seventeenth century according to the classical design prepared by Tibaldi.

1645: Gothic Façade Adopted

Carlo Buzzi designed a new façade in the Gothic style that was adopted in 1645. Tibaldi's classical portals and lower windows, whose construction had already been begun, were retained.

1682: Old Façade Removed

The old façade of Santa Maria Maggiore was removed in 1682.

1767-70: Main Spire Built

Francesco Croce built the spire above the Tiburio between 1767 and 1770. A colossal sculpture of the Madonna stands at the top.

1805-12: Façade Completed

Napoleon ordered the façade's speedy completion and pledged, but did not deliver, funding.

19th century: Roof and Projecting Structures Completed

The flying buttresses, pinnacles, spires, and terraced roof were completed in the nineteenth century.

PLAN

Extra Side Aisles and Clerestory Windows

Milan Cathedral, like its predecessor Santa Maria Maggiore, has two side aisles on each side of the nave instead of the traditional single aisle.

The extra aisles add not only more floor space but also a second change of roof level, making it possible to have a second row of clerestory windows on each side.

Modular Basis of Plan

The cathedral's plan, which is often credited to Simone da Orsenigo, the first chief engineer, is based on a module of 16 braccia. This dimension defines the side-aisle width, and twice this dimension equals the nave width.

Significant Numbers

The building's dimensions incorporate numbers that are significant to Christianity. 144 occurs in a description of an ideal vision of Jerusalem in the book of Revelations (New Testament). Both the length of the nave and the width at the transept are 144 braccia, which is nine times the module of 16.

The number of certain building components also corresponds to significant numbers. 52, the number of weeks of the liturgical calendar, corresponds to the number of free-standing piers.

Rectangular Vaults

The central vaults of Milan Cathedral are short and rectangular like the central vaults of northern churches instead of deep and squarish like those of Italian churches.

GOTHIC FEATURES

Rayonnant Style Apse

The apse, designed by Nicolas de Bonaventure around 1389, reflects the influence of the Rayonnant style, a late phase of the Gothic style typified by large stained-glass windows framed by minimally sized piers and by elaborate tracery formed by slender curved stone bars. All together, these features create a very luminous impression of more glass than wall, which is best enjoyed from the inside the apse and choir.

Piers Decorated by Sculpture

The piers were designed by Giovannino de Grassi.

The capitals are unusual in being composed of niches containing statues on eight facings and in being twenty feet high, which is exceptionally tall.

Because of their large size, prominent horizontal moldings, and multiple-niche design, these capitals interrupt the upward sweep of the piers. The extent of this interruption can be appreciated by comparing these piers with the piers of Reims Cathedral, whose capitals are relatively short, and to the piers of St-Gervais-St-Protais in Paris, which have no capitals.

Spires and Pinnacles

The presence of many spires and pinnacles, as well as pointed trim along the roofline, gives the cathedral the spiky profile characteristic of northern Gothic churches.

The weight of the spires and pinnacles pressing down on the piers supporting the ceiling vaults and the flying buttresses contributes to their ability to withstand the lateral pressure exerted by the vaults.

The spires and pinnacles are topped by sculpted figures.

Lantern Trimmed by Spires

The lantern of Milan Cathedral, known as the Tiburio, is located over the crossing.

Among the many architects who were consulted are Bramante and Leonardo da Vinci, who were working in the region for Ludovico Sforza in the 1480s and 1490s.

In 1490, Giovanni Giacomo Amadeo and Giovanni Giacomo Dolcebuono received the commission to build the Tiburio, which they completed in 1500.

Rising above the crossing piers are four spires, which, in combination with the lantern at their center, were intended to symbolize the Four Evangelists around God.

The central spire's octagonal form is reflected on the exterior by the eight pinnacles that stand at its corners and on its interior by an eight-sided domical vault. In both style and engineering, the Tiburio is compatible with the Gothic aspects of the building.

The spire above the lantern was added in the seventeenth century. A colossal sculpture of the Virgin crowns the top.

Flying Buttresses

Flying buttresses brace the piers carrying the central arches and transfer part of the arches' thrust to the outer piers.

The outer piers are ornamented by sculpted figures under canopies.

FAÇADE

Two Styles Spanning Two Centuries

Because the façade's early construction (early 1600s-1645) followed a classical design and its later construction (1645-1812) followed a Gothic design, features of the two styles are sequenced vertically. Classical features such as plinths under the buttresses and pedimented door and window trims are at the bottom, and Gothic features such as pointed arches, tracery, crockets, pointed gables, and pinnacles, are at the top.

Wider-than-Tall Proportions

Although the cathedral employs Gothic structural engineering and is comparable to Northern cathedrals in nave height, the façade is proportionately wider than that of a northern cathedral.

The extra width added by a second aisle on each side makes the pitch of the roofline less steep.

Horizontal Accents

The building's verticality is also compromised by ornament that creates horizontal accents.

A strong horizontal accent is added by moldings capping pedestal bases, which are 23 feet high. On the façade, this takes the form of plinths at the bases of the buttresses. The shelf-like potential of the plinths is affirmed by their serving as platforms for sculpted figures.

The classical door and window trims also add horizontality, which can be appreciated by comparing the lower part of Milan Cathedral to the lower part of a northern Gothic church such as Saint-Ouen in Rouen.

Prominent horizontal bands of blind tracery are formed by placing the tracery decorating the buttresses at the same level as the tracery ornamenting the galleries, so that together, they form a continuous horizontal pattern.

The reliefs of the figures and emblems decorating the lower part of the buttresses are also arranged in rows, and the vertical areas between them are plain except for slender vertical moldings trimming the whole buttresses.

Milan Cathedral

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back