Garden Design

ANCIENT ROMAN INFLUENCE

Humanism

The development of gardens in the Renaissance, like that of Renaissance architecture in general, was profoundly influenced by humanism, especially as it pertained to ancient Roman villas, which were known primarily through literature.

The Roman Appreciation of Nature

Garden scenes like the paintings decorating the walls of Livia's villa at Primaporta reveal the Roman delight in the natural world of plants and wildlife. The backgrounds in the Odyssey series demonstrate not only an appreciation of the beauty of the natural world but also a sensitivity to the subtleties of distance perception.

Private Gardens

Wealthy Romans maintained residences in both the city and the country. Statues and fountains were common ornaments.

●Peristyle gardens. The city home of affluent Romans, the domus, contained a peristyle garden.

●Villa gardens. Roman villas included many sophisticated garden features like grottos, nymphaeums, and topiary (shrubbery that has been shaped by clipping). "Seaside villas" were a type of villa whose plans were coordinated with the site's topography.

Public Gardens

During the empire, the imperial bathhouses came to include park-like settings with trees and gardens.

Sources of Knowledge of Roman Gardens

Because the Roman empire collapsed around a thousand years before the Italian Renaissance, little evidence of their gardens remained, and information about them was scarce.

●Documents. Vitruvius' treatise on architecture addressed farm villas but not pleasure villas, and consequently, the letters of Pliny the Younger, an affluent patrician whose letters described his own villa at Laurentinum, were the most important source. Pliny expressed an appreciation for the natural landscape as well as for the formal garden. He also discussed the most suitable plants for gardens. An earlier book on the different botanical forms that was written by his uncle, Pliny the Elder, documents the level of knowledge about plants at that time.

●Ancient sites. The actual plantings of the ancient Romans no longer existed, and only their architectural features remained. The largest and best-known Roman villa in the Renaissance was Hadrian's villa, whose ruins include many garden features.

MEDIEVAL GARDENS

Loss of the Roman Garden Tradition

Except for the peristyle garden, which was adapted for monastic cloisters, the Roman tradition in garden design disappeared after the collapse of the Roman empire.

Eastern Developments

While the Roman garden tradition was in decline in Italy, a new garden tradition was developing in the eastern Mediterranean region in conjunction with the newly founded Moslem religion.

Small Gardens within Castle Walls

Because the Italian countryside was a dangerous place in the Middle Ages due to a climate of lawlessness and political instability, the rich lived in fortified castles, and gardens were restricted to courtyard areas within the castle walls. The gardens within castles, which were considered the ladies' domain, were small and devoted primarily to vegetables and a few wildflowers.

Known as a hortus conclusus (enclosed garden), this form was a forerunner of the giardino segreto (secret garden), in the Renaissance.

Symbolism

In art, the garden took on a symbolic value when used in conjunction with the Virgin Mary. In Annunciation scenes, enclosed gardens referred to Mary's virginity.

Garden Imagery in 14th-Century Literature

The poet and humanist Petrarch was one of the first authors to discuss the pleasures offered by the natural world.

In Boccaccio's Decameron, one of the literary harbingers of the Italian Renaissance, the garden of a villa is the setting in which the ten characters pass the time by singing, dancing, and telling stories.

The Fountain of Youth motif that occurred in literature was sometimes presented in connection with an image of a garden of love.

15TH-CENTURY BACKGROUND

Palace Gardens Versus Villa Gardens

The development of what is now known as the Italian garden began in the fifteenth century with the revival of the villa form, of which the garden was an important component.

Few city palaces had enough space for gardens, which were generally small and surrounded by other palaces. An exception is the Pitti Palace, which occupied a large tract on the outskirts of Florence.

As time went on and the conspicuous display of personal wealth became more common, gardens, especially those of villas, became larger and more extravagant.

Importance of Architecture in Gardens

Architecture formed the structural basis of many of the garden's features. Retaining walls, pathways, and monumental staircases were especially important in Renaissance gardens.

Gardens in 15th-Century Pictorial Art

In religious art, the garden was the traditional setting for the Annunciation and Jesus Christ's Agony in the Garden. St. Francis, who was known for his love of nature, was often depicted in an outdoor setting.

In scenes illustrating mythology, nature is often depicted. The background of Botticelli's Primavera is one of the most meticulously rendered paintings of nature in the Renaissance. Over forty varieties of plants are depicted.

Images of outdoor banquets are sometimes contained within mythological scenes such as narratives by Botticelli and his followers.

Colonna's Fictional Garden

A particularly important influence on garden design was a work of fiction that is generally attributed to Francesco Colonna, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, which was published in Venice in 1499 and illustrated by woodcuts. The word "hypnerotomachia" is a fusion of three word roots: "hypn" (dream), "eroto" (love), and "machia" (fight), and "Poliphili" (Poliphilus) is the name of the narrator. The title can be translated as the Dream of a battle for love fought by Poliphilus.

In the book, Poliphilus describes a dream in which he pursues his lady love through an elaborate garden with statues, fountains, and many unusual features. The garden was laid out in concentric circles, and at the center was a round island on a circular lake. At the island's center was a fountain of Venus, the goddess of love, who casts a spell of love on those who draw near.

ALBERTI'S INFLUENCE

Alberti's Treatise

Alberti's ideas on garden design were extremely influential because he was the first person in the Renaissance to write on the subject. In his treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria (On the Art of Building), he approached architecture and garden design by looking to ancient models and documents like Pliny's letters.

Site

Alberti recommended that the villa and its gardens be located on a hillside overlooking a scenic view, much as "seaside villas" in Roman times had been.

Orientation

The orientation of features were to be planned in accordance with the sun and the seasons.

Grottos and Topiary

Alberti recommended using certain features like grottos and topiary, which had also been used in Roman times. He included suggestions about suitable materials.

GARDENS AS SOURCES OF PLEASURE

Sensory Stimulation

Many features of Renaissance gardens were calculated to bring pleasure by stimulating the senses. The idea of sensory stimulation is celebrated by water flowing through the sense organs of a stone mask at the Fountain of the Mask of the Senses at the Villa Farnese.

●Views. Gardens were designed to appeal to the eye at all distances. Formal gardens were often symmetrical and planned to provide vantage points along the central axis from which to view multiple features. Alberti advised planning an indirect route up to the highest vantage point so that the view would be a surprise.

●Sounds from running water. The sounds of running water in gardens ranged from the trickling of small streams to the roar of waterfalls. As visitors moved through the garden, the loudness of the different sources of running water constantly changes, forming a symphonic mixture of sounds.

●Sounds from birds singing. Because the singing of birds provides one of the joys of being in a garden, aviaries were sometimes included to provide the sound of birds singing. At the Villa Lante, aviaries at the upper end originally provided the profusion of bird sounds that was integral to the garden's theme of the evolution from primeval, unspoiled nature at the summit to formally structured garden art at the lower end.

●Scents from plants. Many plants were selected for the fragrance of their flowers or foliage.

Emotional and Intellectual Stimulation

The emotions and intellect were stimulated by certain features and aspects of Renaissance gardens.

●Controlled surprise. A taste for controlled surprise and even bewilderment led to the creation of such features as mazes and trick water jets. Fountains and grottos were among the many features intended to elicit wonder and surprise.

●Themes. Visitors were stimulated mentally by the presence of themes underlying the imagery and layout of the garden. One of the themes at the Villa d'Este concerns Tivoli, Rome, and their rivers. The feeding of Tivoli's rivers into the Tiber before it reaches Rome is symbolized by a long fountain that links a fountain symbolizing Tivoli to one representing Rome.

OPEN-AIR FEATURES

Walls and Gates

Renaissance gardens were enclosed by high walls to insure privacy and security. Walls were sometimes opened by niches containing sculpture.

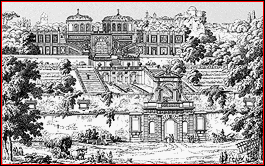

Gates were used within gardens to separate its parts and in outer walls to serve as entrances. Having garden entrances enabled the villa's owner to admit visitors without being personally disturbed in his private dwelling.

Gates also played a significant role in the architectural compositions of many gardens.

Garden gates were sometimes fanciful, which alluded to the imaginative realm within the garden.

Retaining Walls

Retaining walls are walls that hold back earth on one side. Their use was critical to terracing hillsides and building open staircases and ramps. Numerous retaining walls would have been required to realize Raphael's proposed terracing of the Villa Madama.

With the use of terracing and subterranean rooms in the sixteenth century, the land and the architecture became increasingly intertwined.

Allées

Allées are long, straight walkways through a garden. They are surfaced with materials that are suitable for pedestrian traffic such as grass or gravel.

Large gardens often had a number of allées.

In the Renaissance, allées were usually defined by hedges, groves, or other landscaping features, and their terminal points were often large, well-defined features like large statues, fountains, or obelisks. When an allée traversed sloping land that had been terraced, focal points in a series were often placed at the centers of the levels.

Terraces

The term "terrace" refers to a level area that is paved and above ground. "Terracing" refers to creating a series of level areas along a hillside.

A terrace around the residence generally provides a zone from which excellent views of the garden can be enjoyed. Balustrades with urn-shaped supports often formed railings along the terrace's edges.

After Bramante introduced terracing at the Vatican with a thousand-foot stretch known as the Belvedere Court, terracing was commonly used in landscaping large sloping sites.

Open Staircases and Ramps

The widespread use of terracing in the sixteenth century fostered the development of monumental staircases, which were generally integrated with fountains or sculpture. At the Belvedere Court, Bramante built monumental open staircases in three different forms: a straight, wide staircase, a pair of ramped staircases extending across the court, and a circular staircase that was divided into concave and convex halves. In the mid-sixteenth century, Michelangelo popularized the double-ramped staircase and its use with river gods, and this combination was later used in gardens such as the Villa Lante and the Giardino Grande.

PLANTS AND PLANTINGS

Plants Selected for Visual Qualities

A variety of plants and trees were used in Italian gardens. Plants with dense foliage like boxwoods were often used because of their ability to form borders and patterns with distinct edges and to be clipped into regular shapes like balls. Flowering plants were popular in the beds of parterres.

Plants Selected for Functional Qualities

Plants were also selected for their functional qualities. Herbs for the kitchen and medicinal plants for making drugs were commonly included in gardens. Rare plants from newly discovered parts of the world such as America were valued, and plant specimens joined antique coins and manuscripts as subjects of the Renaissance passion for collecting.

Trees

Both deciduous and evergreen trees were planted. Groves of fruit trees were included at many villas. Frequently used ornamental evergreens included cypresses, which are tall and thin, and stone pines, which are also called “umbrella pines” because of their rounded-top, flat-shaped canopies.

Parterres

A parterre is a level section of garden near the house that is usually divided into beds and planted in patterns. Their patterns are usually best seen from the upper windows.

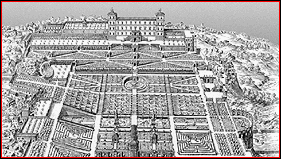

In the Renaissance, parterres were usually aligned with the central axis of the main structure. Especially large villas might have several parterres.

LABYRINTHS

Description

Labyrinths, which are better known as mazes, were generally subsections of large gardens like the Villa d'Este at Tivoli or the Villa Lante at Bagnaia. None survive today because the original plants have died.

They were distinguished by both the character of the plants and the pattern they formed. Shrubs with dense foliage like boxwoods were planted close together and trimmed into hedges. Their layouts were intended to bewilder visitors, who were forced to make many turns as they passed through hedge-lined corridors of green that were too tall to see over.

Because maze patterns were similar to elaborately patterned parterres, it is sometimes hard for modern art historians to distinguish between intentional labyrinths and elaborately patterned hedges.

Origin

The idea behind the first documented labyrinth, that of Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga in Rome in 1479, was to temporarily turn the guest into Theseus, the mythic Greek hero who was faced with escaping from a maze after killing the Minotaur (monster with the body of a man and the head of a bull) kept there by the King of Crete. Theseus escaped from the maze by retracing his way along a thread given to him by Ariadne, the king's daughter.

Labyrinths were admired not only for their ability to confound visitors but also for the cleverness of their geometric patterns.

Publications on Labyrinth Designs

An early Renaissance text on labyrinth designs was written by Giovanni Fontana and published around 1420.

Labyrinths are discussed in Renaissance treatises on architecture. They are mentioned in Alberti's De re aedificatoria, written around the middle of the fifteenth century. Labyrinths are also illustrated in Serlio's Tutte l'opere d' architettura et prospetiva, written in the second quarter of the sixteenth century. Serlio's designs include a loop motif called a "knot."

Influence

Judging from the many examples of mazes in Baroque gardens in England, they seem to have been more popular there in the Baroque and Rococo periods than they had been in Italy during the Renaissance.

16TH C. ORGANIZATIONAL PRINCIPLES

Overview

By the early sixteenth century, several common principles governed the planning of most large villa gardens.

Coordinating Garden and Main Residence

Buildings and gardens were increasingly planned together. Whole gardens or their parterres were commonly aligned with the main residence's central or lateral axis.

The main buildings were designed to maximize enjoyment of the garden. Upper-story rear windows overlooked gardens, and loggias on the ground story provided direct access to them.

Dividing Areas into Four or Five Parts

Rectangular or square parterres or terraces were commonly divided into four quadrants. Inner corners were often rounded inward to form a circular compartment in the center, which generally contained a fountain, sculpture, or some other accentuated feature. Four- or five-part subdivisions were commonly used both within the individual quadrants and within individual beds.

Contrasting Wild and Cultivated Areas

Gardens in the countryside were usually composed of areas of two different characters, one geometrically structured and one seemingly wild and natural. The contrast between the two was considered a virtue because each acted as a foil to the other.

Natural areas were often used to separate formal areas from each other and from other properties.

In cultivated zones, the plantings were geometrically organized into regular configurations. Trees were planted at regular intervals in straight lines, and shrubbery was often clipped to create patterns.

Creating Secret Gardens (Giardino Segreto)

The giardino segreto ("secret garden") is distinguished not by its design but by its placement in locations that provided privacy. Typically, secret gardens were located in close proximity to the residence, usually directly behind it, to ensure privacy and protection.

A secret garden could be the sole garden of a palace or a subsection of a large villa, where it could be isolated by walls, tucked away from the central features, or made inaccessible by a remote location.

Rare and valuable species of plants were often cultivated in secret gardens. It was usually reserved for the owner and his special guests.

Private garden retreats had precedents in such earlier gardens as Hadrian's island retreat at his villa at Tivoli and the hortus conclusus (enclosed garden) of medieval castles.

SHELTERING FEATURES

Overlapping Terminology

When referring to garden architecture, the terms casino, pavilion, and loggia are sometimes used interchangeably.

Casinos

Although the term "casino" can be applied to a villa's main building, it usually indicates a secondary structure. Casinos (Italian pl. = casini) frequently housed collections of objects and were used for social gatherings, which often included music and dance.

Pavilions

A pavilion usually refers to a detached structure in a garden. Like casinos, they were used for social gatherings.

Pavilions were often elevated, which made them excellent vantage points. Their architectural components often included balconies and loggias.

Loggias

Loggias, (loggie in Italian) which were generally incorporated into other structures, created transitional spaces between the inside and outside. They were also built as corridors connecting separate buildings. Renaissance loggias were generally formed by arcades, but colonnades were also used.

Loggias in garden architecture were often used as galleries to display sculpture. Many antique works were originally displayed in the loggias of the Belvedere Court, which were later filled in for stability.

Pergolas

Pergolas are arbors or openwork structures consisting of parallel colonnades or arcades that are connected by an openwork of crossbeams or arches. The openwork at the top, which functions as a trellis, distinguishes pergolas from loggias, which have roofs.

When covered by foliage, pergolas provided both shade and privacy. Climbing roses were popular for pergolas in gardens, and grapevines were common at farm villas where wine was made.

In large gardens, pergolas were often used in conjunction with pavilions, from which they extended on all four sides to form a cross-shaped pergola.

Grottos

A grotto is an artificial cave-like structure (grotta means "cave") that was intended to imitate natural cavities like those found on the islands of southern Italy. Their rough textures imitate such surfaces as natural rock, rock embedded with shell, lava, and stalactites.

Alberti recommended building grottos of a soft, textured stone like pumice, and then coating the surfaces with green wax.

Grottos ranged in size from small niches embedded in walls to multi-room complexes. Often, they consisted of single rooms within a pavilion, and many were located below ground or in windowless spaces.

Grottos often contained elaborate sculpture. Sea creatures were especially popular subjects.

Nymphaeums

A nymphaeum is a retreat for relaxation that is decorated with fountains, plants, and sculpture. The name is derived from "nymph," a minor female nature goddess associated with woodlands and water. In Roman times a nymphaeum was a pleasure house.

AQUATIC FEATURES

Hydraulic Devices

The greatest attractions in most gardens were the fountains. Because Italian fountains were the most highly developed in Europe during the Renaissance, Italian hydraulic (pertaining to water power) engineers were sought by many of Europe's princes.

Hydraulic features included not only visual spectacles like fountains and cascades but also acoustically active built-in devices such as organs and bellowing creatures.

Passage of Water through the Garden

Many Italian gardens were planned in a linear manner in which a central channel of water flowed downward from one fountain to the next.

Pools

Pools functioned as basins to catch the water from fountains and cascades. They were usually totally or partially sunken below the ground level and surrounded by low walls. Many were stocked with fish to make them suitable for fishing.

Fountains

Fountains utilized hydraulic devices to force water to gush from spouts under pressure. The water was delivered in a variety of forms like jets that reached upward to great heights. The collision between falling water and water that is surging upward creates a fine spray of droplets.

Streams of water poured from the mouths of masks, dolphins, and dragons and from the nipples of fertility goddesses and sphinxes (mythological creatures with animal bodies, bird wings, and human heads and chests).

Cascades

Cascades were formed by water overflowing its containers. Cascading fountains ranged in size from tiered fountains, which were composed of a series of basins that were smaller at the top, to waterfalls, whose elevation intensified the sight and sound of splashing.

Water-Chains (Catena d'Acqua)

Water-chains (catena d'acqua) were made by channeling water through a series of compartments in a line until it eventually ended up in a small pool. Especially well-preserved examples exist at the Villa Lante at Bagnaia and the Giardino Grande of the Villa Farnese at Caprarola.

Water Jokes (Giochi d'Acqua)

The Renaissance fondness for surprises with water (giochi d'acqua) was realized by various means of water jokes that wet the guests.

●Spouts hidden in the ground. At the Grotto of the Animals at the Villa Medici at Castello, jets of water shoot out of the ground when activated by visitors' stepping on a triggering mechanism.

●Moving spouts in trick statues. Colonna's fictional work, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, contains a description of Poliphilus being fooled by a trick statue. After seeing water flowing into a basin from the penis of a sculpture of a little boy, Poliphilus attempted to fill a vessel from the stream, but his weight on a stone near the fountain activated a change in the penis' position so that he was squirted in the face.

●Troughs in stone dining tables. The stone dining table at the Villa Lante in Bagnaia contained jets of water in the center that would fill a trough-like depression for chilling wine. The water level could be raised to the point of flooding the table top, which provided a very practical way to clean the table between courses as well as to surprise the guests.

GARDEN SCULPTURE

Places Where Sculpture Was Used

Sculpture in Renaissance gardens was usually integrated with fountains, staircases, and garden walls. Relief sculpture and busts, both ancient and reproduction, were sometimes incorporated into the walls of buildings by antiquarians.

Subjects from Classical Mythology

Many of the themes and subjects used for garden sculpture were based on deities from Classical mythology, which fall into two categories.

The earliest were a group of deities and super-beings who were identified with the earth and its features such as rivers and seas.

The group of gods known as the Olympians evolved later in ancient mythology and continued alongside the early nature gods, and in some cases, merged with them.

Early Nature Gods

The early nature gods evolved in the context of creation myths explaining the origin of the physical world. Gods identified with rivers and seas were especially popular for fountains.

●Oceanus. Oceanus is the Titan in ancient mythology whose domain was the outer sea enveloping Earth. Oceanus was married to his sister Tethys. Their sons were rivers, and their daughters, called "Oceanides," were springs, ponds, and lakes.

●River gods. River gods were typically personified by bearded male figures, who were generally posed in reclining positions. They symbolized individual rivers like the Tiber in Rome or the Nile in Egypt. In the late sixteenth century, pairs of river gods, whose reclining positions made them somewhat triangular in shape, were sometimes placed in front of double-ramped staircases, whose shape is similar. (This combination had been used at mid-century by Michelangelo in front of the Palazzo Senatorio.)

●Nereids. Nereids are sea nymphs whose name was derived from their father Nereus, a pre-Olympian sea god. As daughters of the sea, they often accompanied the later gods associated with the sea such as Neptune and Venus.

Olympian Gods and Associated Beings

The Olympian gods are named for their dwelling place, Mount Olympus. In Renaissance garden sculpture, the following are the most commonly represented Olympians and associated beings.

●Jupiter and Juno. Jupiter (Zeus in Greek mythology), was the supreme god of the Roman pantheon. He was known for having a series of affairs that he tried to conceal from his wife Juno (Hera in Greek mythology) by appearing in such forms as a bull (with Europa), a swan (with Leda), a shower of golden rain (with Danaë), and an eagle (with Ganymede).

●Neptune and the Tritons. Neptune, derived from the Greek god Poseidon, was a son of Jupiter and ruler of the seas. The trident is his principle attribute. Neptune is often accompanied by sea creatures such as the Nereids and his own fish-tailed grandsons, the Tritons, who are named after their father, his son Triton. Tritons were often depicted blowing conch shells or frolicking with Nereids. In mythology, Neptune affected the destinies of mortals by sending storms or sea monsters. On one occasion he demanded that the Ethiopian princess Andromeda be offered to a sea monster under his control after her mother boasted of being more beautiful than the Nereids. It is from this fate that Perseus rescued Andromeda, a scene re-created at the Isolotto of the Boboli Gardens.

●Apollo, the Muses, and Pegasus. Apollo, another of Jupiter's sons, was the god of poetry and music. He consorted with the nine Muses, who were served by the winged horse Pegasus. Because the garden was a place of romance, imagination, and intellectual activities, Apollo, the Muses, and Pegasus were often the subjects of garden sculpture. The placement of a fountain featuring Pegasus and the Muses near the original entrance of the Villa Lante announced to visitors that they were entering a realm of fantasy inspired by poetic inspiration.

●Venus and Cupid. Venus (Aphrodite in Greek mythology), a daughter of Jupiter, was the goddess of love and beauty. Her legendary birth from the sea made her an apt subject for aquatic display. When at sea she is often accompanied by Nereids and Tritons. Her most frequent companions are cupids, who morphed into putti in the Renaissance. Because of Venus' link to the sea, cupids and putti sometimes hold dolphins.

●Diana. Diana (Artemis in Greek mythology), another of Jupiter's daughters, was usually depicted with a bow and quiver. She was a popular figure in gardens as both a protector and a hunter of wildlife. In the eastern Mediterranean at Ephesus, she was worshipped as a multi-breasted fertility goddess.

●Hercules and the 12 Labors. Hercules (Heracles in Greek mythology) was the son of Jupiter and a mortal woman. Although he was deified, given the status of a god at his death, Hercules is generally classified as a "hero" because he was mortal. He wears a lion-skin in reference to one of his "Twelve Labors," his most famous accomplishments. These were done as a penance for having killed his children in a fit of madness sent by Juno, Jupiter's jealous wife, who hated Hercules because he was the offspring of one of her husband's affairs. The eleventh labor of stealing three golden apples from Juno's garden, the Garden of the Hesperides, is referred to in many gardens. At the Villa d'Este, the Dragon Fountain refers to the dragons guarding Juno's garden, and the Fountain of the Owls displays golden apples on its columns. In addition to being known for the Labors, Hercules was an important exemplar of virtue and courage in the Renaissance. In an episode in his youth known as the "Choice of Hercules," Hercules was offered a choice between a life of ease and pleasure versus one of virtue, struggle, and fame. He chose the latter.

Iconographic References

Mythological figures were sometimes symbolic of patrons. For instance, at the Villa d'Este, the frequent references to Hercules referred to the Este family because several of its important members, including the patron's grandfather and brother, were named Ercole, the Italian version of Hercules. At the Villa d'Este, Hercules is referred to not only by images such as the apples and guardian dragons from Juno's garden but also by the garden's design, which forces visitors to choose between multiple routes through the garden, paralleling Hercules' choice between a life of virtue and struggle or one of ease and pleasure.

Apennine Figures

Apennine figures like the colossal example at the Villa Medici at Castello by Ammannati were personifications of the Apennine Mountains. Originally, a spout in the head would have produced a flow of water running down the body that symbolized melting of the snow-capped peaks. A whole-body Apennine figure by Giambologna can be found at another Medici villa, the Villa Medici at Pratolino.

COLLECTION GARDENS

The Orto Botanico

The Italian term "orto" refers to both a kitchen garden and a botanical garden.

A collection garden, also called botanical garden, is a type that was distinguished by the selection and organization of its plants. Plants were usually arranged according to such properties as their origin, genus, or medicinal value.

Collection gardens existed as both self-contained gardens and subsections of large gardens.

Collecting as an Activity

The fifteenth century marked the beginning of large-scale collecting in Italy. It was fashionable to possess examples of many types of things including plant specimens. Consequently, a part of many large gardens included an area devoted to indigenous and exotic plant specimens.

Discoveries Related to Botanical Knowledge

Two botanically related discoveries stimulated interest in the scholarly study of all forms of nature.

●Discovery of antique texts. Ancient texts such as Pliny the Elder's Natural History were discovered and carefully studied.

●Discovery of new plants. The opening of new trade routes to the Far East and the Americas led to the discovery of many new types of plants.

Examples of Collection Gardens

Two outstanding collection gardens that were totally dedicated to specimens rather than being parts of larger gardens were the Orto Botanico in Padua and the Orti Farnesiani in Rome.

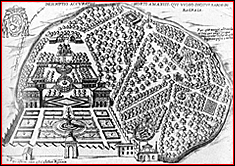

♦Orto Botanico, Padua. The Orto Botanico in Padua was the first of the collection gardens. Its plan was based on a circle, a favorite shape in the Renaissance.

♦Orti Farnesiani, Rome. The Orti Farnesiani in Rome was designed by Vignola for the Alessandro Farnese. It occupied part of the Palatine Hill, which had been occupied by imperial palaces that overlooked the forum in ancient times.

ITALIAN INFLUENCE ON LATER GARDENS

Baroque Gardens

The formal tendencies in garden design defined in the Renaissance reached their ultimate form in Italy during the Baroque period.

Italian gardens, like Italian architecture in general, led the way in garden design in the seventeenth century. Garden features such as elaborately patterned beds and large parterres were carried out on a grandiose scale in France at Versailles, in England at Hampton Court Palace, and in Austria at Schönbrunn Palace.

Eighteenth-Century Reaction

The extreme artificiality of such gardens stimulated a movement in eighteenth-century England that culminated in the development of a more natural form of garden, which is known as the "English garden."

English garden designers like William Kent eschewed the symmetrical, terraced layouts of Italian garden architecture. In the creation of picturesque accents in natural-looking landscapes, English landscape architects copied Italian architectural forms like ancient Roman temples and Palladian bridges. At Stowe, these forms were re-created by William Kent's Temple of Ancient Virtue and Palladian Bridge. The use of picturesque architectural accents peaked at Stourhead, where several structures could usually be seen at once.

The English garden and its use of Italian-inspired architectural accents was highly influential in Europe. On the grounds of Versailles, for instance, a circular temple modeled on ancient prototypes stands in an area of natural fields.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back