Centralized Religious Structures

BACKGROUND

Definition of "Centralized"

"Centralized" or "central plan" refers to a type of design that is organized around a vertical axis and can be circumscribed within a circle. This form is distinct from the axial plan, which is organized around a longitudinal axis.

Historical Precedents

In ancient Roman times, centralized structures were used for tombs and temples. Temples were usually encircled by a peristyle, a famous exception being the Pantheon, which was the most admired building of antiquity in the Renaissance.

In Early Christian times, centralized plans were used for martyria and churches, which often contained tombs. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem originally included an open-air circular enclosure that encompassed the supposed burial site of Jesus Christ. After the original structures were destroyed by Eastern conquerors, Crusaders built a large rotunda over the site.

In the Middle Ages, the axial plan became the standard for churches, and the central plan was largely used for baptisteries and chapels.

In the Renaissance, a number of older centralized buildings were erroneously believed to be ancient Roman temples. These included the Temple of Minerva Medici, which was actually part of an imperial Roman villa, and the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, whose misidentification as the Temple of Mars prior to being used as a baptistery was based on an unsubstantiated belief that the foundation dated to the fourth century.

Inherent Problems

From a functional point of view, there were two main problems with centralized structures: where to place the altar and how to provide separate areas for clerical and lay participants. The predominant use of the axial plan reflected its inherent suitability for the processional aspect of religious services and its logical divisibility into two parts.

Solving these problems in centralized structures usually required some degree of modification such as locating the altar in a chapel opposite an entrance vestibule. These projections were often balanced on each side by additional chapels.

Votive Churches

Many of the centralized churches built in the Renaissance were votive churches, and as such, their primary purpose was to accommodate the stream of pilgrims who came to visit sacred relics rather than to conduct services that satisfied the needs of the local community.

Because the centralized plan was organized around a single point, its choice was a natural one for churches and chapels that were built over the particular place. For instance, the Tempietto is centered over the exact spot where St. Peter was believed to have been crucified, and the crossing of St. Peter's is located over the crypt in which he was buried.

THEORETICAL BASIS

Intellectual Basis of Church Design

The intellectual and humanistic character of Renaissance architecture is especially evident in the design of centralized churches.

Harmonic Proportion

At the heart of the impetus to design centralized churches was the notion of designing after Nature, meaning the universe. According to the concept of harmonic proportion, the universe was seen to have a mathematical basis. Consequently, designing after Nature meant incorporating shapes that were geometrically derived and proportions that were in harmony with each other and the whole.

Centralized Design as a Reflection of Deity

Because God was seen as the creator of a universe whose physical laws embodied an internal harmony that could be expressed mathematically, it followed that the most suitable forms for churches would be those that mirrored God's mathematical perfection.

Because all its points are equidistant from its center and it has neither beginning nor end, the circle was regarded as the most perfect of all plane figures, and therefore, the most fitting as a basis for buildings dedicated to the worship of God.

TREATISES ADDRESSING CHURCH DESIGN

Overview

Several Renaissance architects and artists expressed their interest in centralized churches in treatises. Although Leonardo da Vinci did not leave a treatise, his thoughts about the design of centralized churches and a wide range of other subjects can be found in his notebooks, which contain a combination of drawings and notes.

Vitruvian Background

The concept of harmonic proportion held great importance for Vitruvius, an ancient Roman architect who wrote The Ten Books on Architecture, a treatise on architecture that was studied by Renaissance architects in search of guidance on ancient principles of design. In his third book on temples, he discussed the proportions of the human body, noting how the human figure with its arms and legs outstretched, fits perfectly into a square or circle, and that these ideal proportions should be reflected in the design of a temple.

Alberti's Treatise Regarding Churches

Alberti's treatise, De re aedificatoria, which was substantially complete by the early 1450s, was read in manuscript form by many architects and humanists before its publication in 1485.

Alberti discussed churches under the category of "Temples," thereby linking them with the sacred buildings of the Classical tradition. He described a number of qualities and features he considered desirable for church design.

Alberti's first requirement for churches was that they embody beauty, which he defined in terms of harmony and proportion.

Most of Alberti's discussion concerned centralized churches, which he considered to be the ideal form. Because the only centralized church Alberti designed, San Sebastiano, was not completed according to his original plan, many of the features Alberti recommended are most visible at Santa Maria delle Carceri in Prato, a church designed by Giuliano da Sangallo, who was influenced by Alberti's treatise.

Alberti, also recommended the use of a portico like that of a Classical temple. In combining this feature with a circular structure, he probably had the Pantheon in mind because centralized Roman temples typically had continuous peristyles without porticos. A classical portico was one of the features Alberti had planned at San Sebastiano.

Francesco di Giorgio's Treatise Regarding Churches

Francesco di Giorgio, who wrote the Trattati, classified churches according to three types: centralized, axial, and composite, which combined the first two. This third type had precedent in late medieval cathedrals such as Florence Cathedral, whose transepts repeat the design of its apse.

Although Francesco di Giorgio's treatise was not published in the Renaissance, its manuscript form was read by several Renaissance architects. Leonardo and Bramante, who both worked in Milan for Ludovico Sforza in the 1480s and 90s, were acquainted with it. Leonardo included composite churches among his drawings for churches, and Bramante added a centralized east end onto the existing axial church of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

Serlio's Treatise Regarding Churches

Serlio's Architettura, which was published in separate books over a period of years, was extremely influential in the sixteenth century and later. Of special importance to church design were the third and fifth books, which addressed ancient buildings and Renaissance churches, respectively.

A predominance of Serlio's examples in both categories were centralized. Like other Renaissance architects, he wrongly classified many ancient round buildings as temples.

Serlio's pictures and text reflect the High Renaissance influence of Bramante and the Mannerist influence of Raphael, Peruzzi, and later architects who were working in the second quarter of the sixteenth century.

Palladio's Treatise Regarding Churches

Like Alberti, Palladio embraced Vitruvius' concepts of beauty and harmonic proportion in his treatise I quattro libri. He held the view that churches should be the most beautiful of buildings and include such features as temple-front porticos, elevated main stories, and locations in spacious piazzas.

When Il Redentore was being planned, Palladio had argued for a centralized design. Although an axial design was specified, he achieved a centralized effect under the dome by limiting the transept arms to apses and screening the monk's choir with a semicircular colonnade. Together, the apses and colonnade form a tri-lobed space.

Palladio's only opportunity to design a centralized church was a chapel at the Villa Barbaro at Maser.

COMMONLY USED GEOMETRIC SHAPES

Circular Churches and Chapels

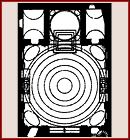

The circle, being considered the most perfect of geometric figures, was incorporated into the designs of many Renaissance churches and chapels.

Brunelleschi's unfinished Santa Maria degli Angeli, whose sixteen exterior sides approach a circle, was the first near-circular church begun in the Renaissance. His design features a central rotunda surrounded by eight compartments.

A circular basis was also used for chancels such as those of Santissima Annunziata in Florence and Santa Maria della Pace in Rome.

Circles were also used for chapels such as the Capella Pellegrini in San Bernadino in Verona by Sanmicheli.

The iconic circular building of the Renaissance is Bramante's Tempietto, a freestanding chapel located in a courtyard of the Monastery of San Pietro in Montorio. The Tempietto is probably the most admired building of the Renaissance.

Deriving Geometric Figures from Circles

A number of regular figures, such as a square, a hexagon, and an octagon, can be derived from the circle using a compass and straight edge. In his treatise on architecture, Alberti described this process, which was illustrated in later printed editions.

Square Plans and Cubic Spaces

A square forms the basis of many small chapels, altar chapels, and rotundas within churches as well as the perimeters of whole churches.

Squares could be used to define dimensions not only horizontally but also vertically. When squares define both the plan and the wall, a cubical shape is formed.

Cubical cores are often evident from the exteriors of centralized churches. Leonardo's sketches for centralized churches include a number of variations in which apses and other projections protrude from a cubical core.

Polygons

Regular polygons (closed, plane figures having three or more straight sides of the same length) often formed the basis of both freestanding and built-in structures.

Octagons were the most commonly used of the non-square polygons. Because of their divisibility into quadrants and compatibility with the right angles of construction, octagons were inherently more compatible with conventional construction than pentagons, hexagons, and decagons.

Octagons could be made into five-sided chapels by cutting off three sides, which made them ideal to use in a series along the outer walls of churches.

The symbolic significance of the number eight, which signified the seven days of Creation plus a day of Resurrection, added to the appeal of octagons for baptisteries, whose decoration often reflected these themes.

Greek Crosses

Greek crosses, essentially squares from which arms of equal length project on all four sides, satisfied the desire for both centralized shape and cruciform symbolism.

On small, simple churches, the Greek-cross form is evident from the outside, but on large, complex configurations like St. Peter's, it is partially obscured by the addition of chapels and other architectural elements.

PAINTINGS OF CENTRALIZED BUILDINGS

Opportunities to Design Ideal Churches

Commissions for paintings with architectural backgrounds sometimes offered artists opportunities to invent ideal centralized structures without regard to the realities of patronage and funding.

Paintings Illustrating Centralized Buildings

The following buildings are among the better known examples of centralized structures depicted in Renaissance paintings.

♦Circular Building in View of an Idealized City, 3rd quarter of 15th century. A circular building stands in the center of a painting of an ideal city, thought to have been a collaboration between the painter Piero della Francesca and the architect Luciano Laurana.

♦Temple in Perugino's Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter, 1481. An octagonal temple dominates the background of Perugino's Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter.

♦Temple in Raphael's Marriage of the Virgin, 1504. A 16-sided building fills the upper space of Raphael's Marriage of the Virgin. This painting precedes his first architectural commission, the Chigi Chapel, by nine years, which suggests that Raphael gave a lot of thought to the design of centralized religious structures while working as an artist.

CENTRALIZED CHAPELS

Overview

Some of the impetus toward centralized places of worship found expression in chapels, which were usually contiguous with the main church. Such additions were often commissioned by wealthy families, who used them for private services and the tombs of prominent family tombs. Chapels often served as sacristies, rooms for sacred vessels and vestments.

Examples

♦Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo, Florence, 1419-28. Brunelleschi's Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo is a domed square with a domed square altar chapel measuring one quarter the size of the main space. Pendentives in both the altar chapel and the main sacristy provide graceful, spherically based transitions from the square bases to the circular domes. Brunelleschi was the first Renaissance architect to use pendentives, which were not previously known in Italy except in the Byzantine architectural tradition of Venice.

♦Pazzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence, 1442-c.1465. Despite the axial quality suggested by the lateral barrel-vaults extending from the domed-square center, the Pazzi Chapel is considered a part of the development of centralized churches and chapels because its volumes are concentrated toward its center and it lacks a nave. Because the lateral extensions are as wide as the square central space, the chapel has a rectangular shape at the floor level.

♦Portinari Chapel, S. Eustorgio, Milan, 1460s. At the Portinari Chapel, a cylindrical drum capped by a conical roof rises from a square base. The domed square design and use of pendentives show the influence of Brunelleschi's Old Sacristy, but the use of boldly patterned polychrome marble to decorate the structural forms obscures the Brunelleschian effect of structural clarity.

♦Sacristy of Santo Spirito, Florence, 1489-96. Giuliano da Sangallo's Sacrisity of Santo Spirito is located beside the church's nave. Its design combines an octagonal plan with an eight-section dome. Its vestibule is vaulted by Giuliano's characteristic coffered barrel vault.

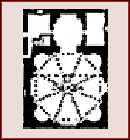

♦Santa Maria presso San Satiro (remodeling of original church), Milan, begun after 1478. Bramante was commissioned to remodel the original ninth-century church of San Satiro as a chapel to a cruciform church that was added in the fifteenth century. The plan is based on a Greek cross whose center is domed and whose arms terminate in apses. On the exterior, this is expressed by the cross of pitched roofs extending from a square core. At the top, an octagonal drum carries the dome. On the ground story, the arms are contained within a circular perimeter, and the spaces at the corners are filled by low chapels.

♦Baptistery of Santa Maria presso San Satiro, Milan, begun after 1478. Bramante's baptistery of Santa Maria presso San Satiro is octagonal in plan. Apsidal niches fill the four corners of the square space it occupies.

♦Tempietto, Rome, designed c.1502. Bramante's Tempietto is composed of a hemispherical dome on a cylindrical core that is encircled by a colonnade. This building is often considered the pinnacle of centralized architectural design in the Renaissance because of its circular form and harmonious proportions. On the interior, a statue of St. Peter occupies a large niche opposite the entrance. In the center is an opening through which to view the crypt. The circular court designed by Bramante was not constructed, and the Tempietto stands in a rectangular court, whose four openings are aligned with it.

♦Chigi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, 1513-16. Around 1513, Agostino Chigi commissioned Raphael to design the Chigi Chapel, a funerary chapel at Santa Maria del Popolo. Its main elements are derived from Bramante's design for St. Peter's, with which it shares the basic structural elements of a hemispherical dome, a cylindrical drum, pendentives, and four piers utilizing Bramante's angled inner facings.

♦Medici Chapel, San Lorenzo, Florence, begun 1520. Michelangelo's Medici Chapel, also called the New Sacristy, forms a mirror-image counterpart to Brunelleschi's Old Sacristy. It is similar to the earlier structure in its plan, its use of pendentives, and its use of materials but different in having a coffered dome, rectangular windows, an upper story, a two-part scheme of stone trim, and many Mannerist elements. The contrast between Brunelleschi's structure-emphasizing austerity and Michelangelo's inventive complexity would have been even greater if the Old Sacristy had been left undecorated as Brunelleschi had wanted instead of being ornamented by Donatello and others.

♦Pelligrini Chapel, San Bernadino, Verona, 1527. Sanmicheli designed the Pellegrini Chapel at San Bernadino in Verona for Margarita Pellegrini in 1527. The chapel consists of a square vestibule leading to a circular rotunda, whose walls are indented by an arrangement of niches.

CENTRALIZED CHURCHES

Comparison with Chapels

Churches were larger and had to serve more functions than chapels. Consideration of the exterior was usually a requirement of churches but often not of chapels, which were often built within or contiguous with churches.

Examples

♦Santa Maria degli Angeli, Florence, 1434-7 (unfinished). Brunelleschi's Santa Maria degli Angeli was planned as a rotunda surrounded by eight recesses. The entrance and altar chapel were to occupy spaces across from each other. Had its construction not been abandoned after a few years, when only the foundation and lower walls were complete, it would have been the first centralized church of the Renaissance. The highly plastic design of the perimeter is composed of piers forming niches on both the interior and exterior. A simplified version was completed in the 20th century.

♦San Sebastiano, Mantua, begun 1460. San Sebastiano, Alberti's only centralized church, is the first church of the Renaissance to be based on a Greek-cross plan. Many of the building's proportions were based on the ratio of 3:5, which approximates the golden ratio. Two decades later, the church was completed under an architect who did not have Alberti's plan or understand classical design principles. Changes include a groin vault instead of a dome at the center and a dog-leg staircase on one side instead of a single wide flight at the front, as Alberti probably intended. It has been theorized that he also probably intended to have six, regularly spaced pilasters. During twentieth-century renovations, flights of stairs were extended forward from the side bays of the vestibule at the front.

♦Santa Maria delle Carceri, Prato, 1485-1506. Giuliano da Sangallo's Santa Maria delle Carceri, a simple Greek-cross plan consisting of four barrel-vaulted cross arms around a dome, was the first church in the Renaissance to be symmetrical on both axes. Simple proportions govern both the plan and section. This church embodies many of the features that Alberti recommended in his treatise.

♦St. Peter's, Vatican, Rome, 1506-98.

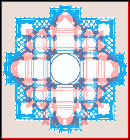

1506-14. Julius II commissioned Bramante to design a new church to replace Old St. Peter's. His first design is known from a medal and a partial plan known as the parchment plan. These two sources roughly correspond in having a number of distinct parts in common. Bramante based the lateral distance between the crossing piers on the width of the nave of Old St. Peter's. By clipping the inner corners of the crossing piers to make them essentially triangular in section, Bramante expanded the size of the crossing square, whose width defined the diameter of the dome. This produced a dome that was wider than the nave, but, unlike medieval equivalents, it only required four piers. The interior was articulated as a single huge story by the use of the colossal order on the massive crossing piers. Bramante's dome, illustrated by a drawing in Serlio's Architettura, was to have been hemispherical in shape and solid core in construction.

1546-64. After the death of Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, who had been the chief architect since the death of Raphael in 1520, Michelangelo was put in charge of the project. He abandoned Antonio's axial plan with entrance towers and returned to a simpler variation of Bramante's apse-ended Greek-cross plan. Michelangelo's detailing of the outer perimeter consists of a rhythmic arrangement of paired pilasters that establish wide and narrow sections of walls. The strong vertical lines direct the eye upward toward the dome and its lantern. The engineering of the dome's support system has been much studied, and its steeper-than-hemispherical proportions are the basis for similar designs in the Baroque period.

♦Santa Maria della Consolazione, Todi, begun 1508. The design of Cola da Caprarola's Santa Maria della Consolazione at Todi, which is located on a hillside, is thought to have originated in Bramante's circle because of its similarity to Bramante's other churches. The use of large apses protruding from a central block was earlier used on the east end of Bramante's Santa Maria delle Grazie. The church at Todi is elegant in its simplicity and unity of forms.

♦Madonna di S. Biagio, Montepulciano, begun 1518. The church of the Madonna di S. Biagio by Antonio da Sangallo the Elder is basically a Greek cross with a domed central square and barrel vaulted arms. The crossing is supported by piers of deeply modeled Doric half columns and pilasters. The one-story apse and the entrance tower, which was designed as one of a pair, give the church a distinct front and rear that is not reflected on the interior. Like its predecessor Santa Maria delle Carceri, which Antonio had worked on with his brother Giuliano, the exterior walls are articulated as two stories by the orders.

♦Sant' Andrea in Via Flaminia, Rome, 1550-53. Sant' Andrea in the Via Flaminia is important as the first church to have an oval dome. Vignola's design is an elongation of the highly popular domed square.

CENTRALIZED EAST ENDS

Fusing Centralized and Axial Churches

Some axial churches are relevant to an examination of centralized churches because their east ends are especially large and centralized in design. Of the three east ends examined below, two are additions to pre-existing basilican churches and one was designed from the beginning.

Examples

Although the following churches have centralized east ends, they are actually axial churches, and as such, they are also discussed in that section.

♦Tribune of Santissima Annunziata, Florence, 1444-76. Michelozzo's remodeling of the Church of Santissima Annunziata in 1444 included the addition of a circular chancel known as the Tribune. Michelozzo originally planned a single-story circular ambulatory around a dome, which would have created a space like that of Santa Costanza. Alberti, who was brought to the project in 1469 by Ludovico Gonzaga, modified Michelozzo's design by widening the dome to cover the part that would have contained an ambulatory.

♦Santa Maria della Pace, Rome, 1478-83. Santa Maria della Pace (Peace) has a chancel that is wider than the nave and separated from it by an opening that is narrower. The nave lacks side aisles and functions as a vestibule to the chancel. The church was commissioned by Pope Sixtus IV as a votive church on the site of a chapel containing a painting that was considered miraculous because its image of the Virgin Mary bled after being stabbed with a knife. On seeing it, the pope vowed he would build a church here as an expression of gratitude for the Virgin's help in ending a war with Florence. The church is best known for two later additions: a cloister designed by Bramante and a façade designed by Pietro da Cortona.

♦Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, rotunda begun 1492. For his rotunda addition to the existing church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Bramante designed a wide dome whose circle-in-square plan follows the tradition begun by Brunelleschi at the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo in Florence. Bramante's addition leaves the fifteenth century stylistically, however, in the organic arrangement of its parts, which are conceived in volumes rather than planes.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back