Villa Madama

Rome, begun 1518

Architect: Raphael

BACKGROUND

Commission

In late 1518 or early 1519 Cardinal Giulio de' Medici commissioned Raphael to design a villa that was to be the largest and most full-featured one planned since Roman times.

It was built on the outskirts of Rome on the slopes of Monte Mario. The site was located a couple miles north of the Vatican.

Giulio enjoyed wealth not only as a member of the Medici family but also as a Cardinal and a cousin of Pope Leo X, who appointed him to many well-funded offices including that of Vice Chancellor.

State of Completion

Giulio's wealth enabled him to fund this undertaking generously, and by 1523, the main apartment and upper-level gardens were ready to be used.

Because of the size of the grounds and number of special features, only a portion of the original design was finished.

The part that was constructed is located on the upper side of the site, where it is nestled into the sharply rising hillside. Less than half of the main building was constructed. During the Sack of Rome, the building was burned, and its current state is due to modern restoration.

Knowledge of Raphael's Design

Knowledge of Raphael's design comes from a number of drawings in the Uffizi, mostly attributed to Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, as well as from a letter in which Raphael describes his plans for the villa. The reconstructions illustrated here were based on a compilation of sources rather than any specific drawing.

HISTORY

1518: Beginning of Construction. Cardinal Giulio de' Medici commissioned Raphael to design the Villa Madama, and construction was begun in 1518. Because Giulio made ample funds available, construction progressed rapidly.

1520: Death of Raphael. Raphael died, and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, who had been the supervisor of the villa's construction, was put in charge of the architecture. Giulio Romano and Giovanni da Udine were assigned the decoration.

1521: Cessation of Work after Leo X's Death. At Leo X's death, Giulio returned to Florence, and work on the villa ceased.

1523: Resumption of Work after Giulio's Election. By 1523, the apartment and garden loggia had been decorated and were ready for use. After Pope Hadrian VI died, Giulio was elected pope, becoming Pope Clement VII. Construction resumed, but its pace was slow because he allocated much of his budget to building St. Peter's.

1527: Sack of Rome. During the Sack of Rome, the villa was pillaged and partially burned. Clement VII observed the smoke from the villa's burning from his refuge in the Castel San Angelo.

1534: Death of Pope Clement. Clement VII died in 1534, and the Medici family acquired the villa from the Church. The property went first to Ippolito de' Medici, and after his death in 1535, to Clement's illegitimate son, Duke Alessandro de' Medici.

1537: Ownership by "Madama." Alessandro de' Medici was assassinated in 1537, and the villa and much other Medici property passed to his wife, Margaret of Austria (1522-86), an illegitimate daughter of Emperor Charles V. Margaret's being referred to as "Madama" is the source of the villa's name.

1538: Ownership by the Farnese Family. In 1538, Margaret of Austria married Pope Paul III's grandson Ottavio Farnese, the Duke of Parma, and the villa became Farnese property. Upon the death of Paul III in 1549, the villa was returned to Catherine de' Medici, Queen of France, who eventually gave it to Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in 1555, and it remained under Farnese control from that point forward. (Margaret is also known as "Margaret of Parma" due to this marriage.)

ROMAN-INFLUENCED FEATURES

Re-Creating a Roman Villa

In designing the Villa Madama, Raphael sought to re-create an ancient Roman form rather than to adapt Roman styling to a modern form, which was the usual approach at that time.

For this project, he studied the ruins of Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli and the letters of Pliny the Younger, who described his own villa at Laurentinum.

In planning the decoration, Raphael looked to ruins where wall paintings survived such as the Domus Aurea and the Baths of Titus.

Varied Facilities for Leisure

Many of the facilities for entertainment at the Villa Madama were patterned after features used at ancient villas.

A Roman style theater with semicircular seating and a Roman style stage building had been planned for the rear of the main building. As with ancient Roman theaters, whose concentric tiers of open-air seating were usually built into hillsides to minimize the amount of construction necessary, the seating of the villa's theater would have been carved into the hillside behind the villa.

Also planned but not built was a stadium-surrounded racetrack that resembled a Roman hippodrome.

The garden itself included many Roman-inspired features like a fish pond and a nymphaeum.

Terrain-Oriented Layout

In laying out the Villa Madama's buildings and landscaping features parallel to the rising hillside, Raphael followed the Roman "seaside" villas, whose plans were asymmetrical and coordinated with the site's topography. To create a series of flat areas on the sloping site, Raphael designed a series of retaining walls.

Ground Level as Main Story

Instead of making the piano nobile the villa's main level, as it usually was in the Renaissance, Raphael treated the ground story as the main level, as it had been in Roman times.

Although the sloping site meant that the ground-story level on the high side was the piano nobile level on the low side, the villa was planned so that the main room, the garden loggia, was at ground level. Achieving this required a substantial use of retaining walls.

Large-Scale Vaults of Varied Forms

Except in including pendentives, a post-Roman form, Raphael designed vaulting for the garden loggia using a vocabulary of typical Roman vaults. He combined these vaults to create varied and interesting spaces like those of large-scale Roman buildings such as the imperial baths and the Basilica of Constantine.

Different Parts for Summer and Winter Use

Raphael followed recommendations from Vitruvius and Pliny with regards to the orientation of each part in accordance with its function.

Duplicate quarters were planned to face in two directions, like the summer and winter dining rooms of an ancient Roman domus. Having similar facilities on opposite facings allowed the afternoon sun to be avoided in the summer and enjoyed in the winter.

Only the villa's summer quarters were built.

MAIN PARTS

Original Symmetrical Layout

The summer and winter quarters were designed as similar groupings of rooms on opposite sides of a circular courtyard. If both blocks had been completed, they would have formed a single building with an entrance at the center.

A Roman style theater was to have occupied the rear area behind the circular courtyard.

Circular Courtyard

If the winter quarters had been built, a circular courtyard would have occupied the building's center and connected its parts. The courtyard perimeter was to have been formed by walls rather than loggias. Columns are present, however, in the form of large and small engaged columns, which give the wall rhythm and plasticity.

The sections of the courtyard that were built form wings flanking a doorway.

The use of exposed brick construction is unusual and may have been inspired by similar treatments at Hadrian's Villa.

Principal Rooms

The part of the villa that was built is composed of several rooms.

A vestibule connects the courtyard to the garden loggia, the most admired part of the Villa Madama.

Located on the corner overlooking the falling hillside is the apartment suite. Two bays of the apartment are located next to the garden loggia, where they overlook a fishpond and a parterre.

GARDEN LOGGIA

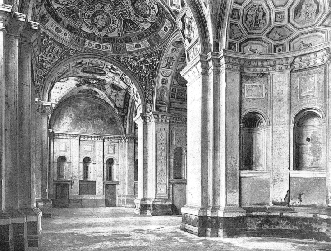

Vaulting

As noted in the section on Roman influence, the vaulting of the garden loggia recalls that of the Basilica of Constantine and the Baths of Diocletian in its monumentality and variation in vault type.

Decoration of Interior

The loggia's decoration, which includes grotesques and other motifs derived from ancient Roman models, was designed by Raphael and executed by his assistants after his death in 1520. The frescos were painted by Giulio Romano, and the stucco work was executed by Giovanni da Udine.

Filling in Arches

To protect the decoration, the loggia openings were filled in later.

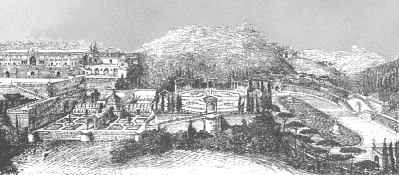

GARDENS

Landscaping beside Garden Loggia

Along the same axis as the vestibule and the garden loggia, a long rectangular plateau was cut into the sloping hillside.

Because of the steepness of the slope, story-high retaining walls were required both to keep the earth back on the mountain side and to support the plateau on the valley side.

The parterre next to the garden loggia was formally landscaped. The end opposite the loggia is enclosed by a high wall, but the side overlooking the hillside is open.

The wall at the far end of the parterre is opened by a large gate. Two colossal sculpted figures stand like guardians beside it.

Water Features

Water from mountain springs originally entered the garden through three fountains built into grottos within the retaining wall on the parterre's upper side. The fountain in the central niche, made by Giovanni da Udine, featured a large elephant head surrounded by shells and mosaics. Little besides the head remains.

Water flowed into a fishpond from a grotto built under the parterre.

Nymphaeum

A nymphaeum was built at the northwest corner of the villa, but most of it has been destroyed.

Features Not Built

Only a small part of the landscaping planned in Raphael's ambitious design was realized.

If completed, more retaining walls like those built on the western side would have created level areas over the whole property. Wide ramped staircases like those designed by Bramante for the Belvedere Court would have been incorporated into some of the walls.

A large parterre would have been built further down the hill. Its center may have included a cross-shaped pergola, a structure formed by pergolas extending in four directions from a pavilion. Similar structures were built at other large gardens such as the Vatican and the Villa d'Este.

The circular space defined by gates and sections of colonnade suggests the inspiration of the Canopus of Hadrian's Villa.

See visual summary by clicking the Views button below.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back