Concrete

BACKGROUND

Definition

Concrete is a mixture of three ingredients: a binding agent called cement, an aggregate, and water, whose presence produces a chemical change in the mixture that transforms it into a rock-hard, continuous mass.

Roman Materials

In Roman times, the binder was made from lime.

The aggregate was composed of caementa, which was made up of broken rock or small stones, and pozzolana, which was a sand made from volcanic ash. Pozzolana, which was named for the town of Pozzuoli, gave Roman concrete much of its strength and ability to withstand leakage when used in water.

Historical Development

Concrete was known in the Near East before the Roman period, but due to the inadequacy of the local materials, it was not developed in this region.

The Roman invention of concrete arose from the practice of using an infill of rubble between parallel brick walls. By the third century BC, the Romans were using an early form of concrete.

In the first century AD, the potential of this material to form curving shell-like structures was explored at Nero's palace, the Domus Area. Because concrete was itself fluid and could take the shape of its mold, it was possible to create plastic forms like the outward billowing lobes of parachute domes.

Types of Structures Built of Concrete

Once the Romans perfected their techniques of using concrete, they used it to achieve large vaulted areas of enclosed space in fluid, non-rectilinear shapes. Among the structures of this type were the imperial palaces as well as public facilities such as bath houses, amphitheaters, bridges, and aqueducts. Concrete was also the dominant material used for several structures of building types not usually constructed of concrete: the Pantheon, Hadrian's Villa, and the Basilica of Constantine.

UTILITY

Advantages

The revolutionary development of a large-scale architecture enclosing space for human activities had been made possible by the introduction of the arch, but the invention of concrete added several other advantages.

●Speed of construction. Space could be enclosed quickly.

●Strength and monolithic consistency. Roman concrete was hard like stone and could withstand the compression of much weight. Once cured, concrete formed a single, continuous mass.

●Resistance to burning. Concrete's ability to withstand fire is another of its advantages.

●Low cost of materials. The cost of quarrying powdered lime and volcanic sand was far less than that of quarrying stone or making bricks.

●Ease of transport. Transporting the components of concrete was far easier than transporting stone from quarries. Although pozzolana was named for the site near Naples, volcanic ash could also be found in central Italy. The main region where lime could be quarried was Tivoli, which was around fifteen miles from Rome.

●Fluid shapes. Non-rectilinear shapes could easily be achieved because concrete's semi-liquid nature enabled it to fill whatever shape was prepared by molds.

Disadvantages

Concrete had several disadvantages.

●Lack of tensile strength. Concrete, like stone, lacked tensile strength.

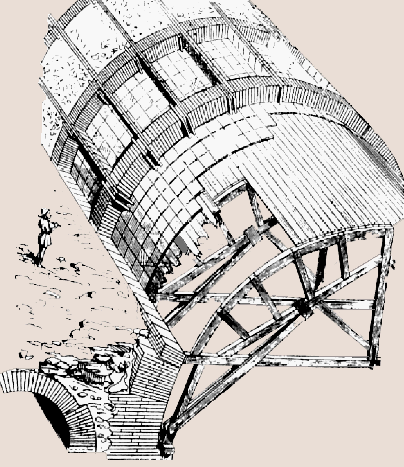

●Expense of centering and form-work. Another expense of concrete was centering and form-work, which required labor to build and the sacrifice of much wood because the centering and forms were usually destroyed during their removal.

●Staining when exposed to the weather. Because exposed concrete became stained unattractively after exposure to the elements, the Romans always covered its surface by stone, brick, or tile.

BASIC TECHNIQUES

Continuous Pour

Roman mastery of concrete included the ability to make a mixture that dried slowly enough that the next pour could be performed before the previous one dried. This continuity resulted in the cured structure being like one giant piece of stone without the weak points that would have resulted from fusing wet to dry areas.

Selection and Placement of Aggregate

Various types of stone were placed at different levels of the pouring. A dense, heavy stone like basalt was used as the aggregate for lower parts of the structure because greater strength was needed there to withstand the load from above. A light, pumice-rich aggregate was used for the upper areas of vaults because lightening the load decreased the downward thrust.

The mass making up the concrete is called opus caementicium. Opus is Latin for "work," and caementa refers to stones that are undressed or crushed, which were used in a rubble-like random fit that was mortared into a solid wall.

TYPES OF FACINGS

Exterior Facings

To avoid the staining that made exterior concrete increasingly unattractive over time, a number of covering techniques were used. Although the most important buildings were encrusted with cut-stone slabs, most structures were covered with a cheaper material like pieces of stone or tile that were pushed into an outer layer of wet mortar. The pieces and their arrangements evolved over the centuries from coarse to refined.

●Opus incertum (2nd century BC - early 1st century BC). Opus incertum refers to a random arrangement of small cut stones of different sizes and shapes.

●Opus reticulatum (1st century BC -1st century AD). Opus reticulatum was achieved by inserting the pointed ends of pyramid-shaped stones so that the square surfaces of the pyramids' bottoms were exposed. These pieces were set diagonally, which formed a regular criss-cross pattern on the wall surface.

●Opus testaceum (1st century AD onwards). Opus testaceum. was formed by using pieces of brick or tile, which were made of terracotta.

●Mosaic. For features involving water such as nymphaeums, mosaic was often used.

Interior Facings

There were several approaches to covering the interior surfaces of concrete walls and vaults. The latter were often coffered during the pouring process by stacking a series of increasingly smaller geometrically shaped forms, which left recessions after removal. As on the exterior, the most expensive treatment was encrustation with a fine-grained stone like marble. Other types of facings included mosaic, gilding, stucco in relief, and frescoes. Common fresco subjects were simulated stone and views of cityscapes or landscapes through openings in fictive architecture.

Add Placemark

Add Placemark Go Back

Go Back